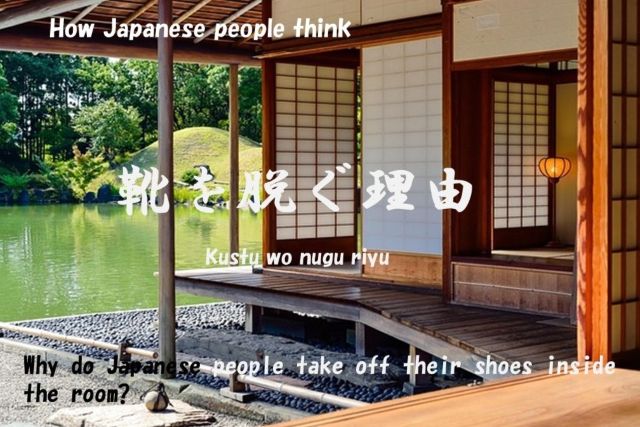

Japan Discovery How Japanese people think “Shoes Off: An Enduring Japanese Custom”

Not wearing shoes inside the house is a givenin Japan. Even as shikibuton(floor mattresses) gave way to beds, tatami(straw mats) to hardwood flooring, and zori(traditional sandals) to shoes, people firmly take off their footwear indoors. This practice has not changed, even with the modernization and Westernization of lifestyles in recent history. Entering a room while wearing shoes, known as dosoku(literally “earth shoes"), is considered a deeply impolite act.

Entering a Beautiful Japanese Home: The Etiquette

Everything in Japan is formal, and even taking off your shoes has its manners and rituals. Children are taught this by their mothers from a young age. Let’s recreate a scene from the Shōwa era (1926–1989) when a mother, Mrs. Yamana, and her daughter, Tomoko, visit a friend, Mrs. Isshiki.

In those days, front doors were often unlocked. The mother would slide open the door and call out to the house.

(Sound of the sliding door opening)

“Hello, it’s Yamana. Excuse us for intruding." (Konnichiwa, Yamana desu. Ojamashimasu.)

Mrs. Isshiki, the friend, quickly rushes out from the back of the house.

“Welcome! Please, come right in, come right in!" (Irasshai,-yō okoshiyasu. Sa~a hayou, agatte, agatte.)

“Thank you, we’ll come up now." (arigatō, agara shite morau wa ne.)

The mother and daughter take off their shoes and step up onto the raised floor (agarikamachi). Three-year-old Tomoko starts to head further into the house, leaving her shoes as they are.

“Wait a minute, Tomo-chan. You have to line up your shoes. Line them up just like Mom did, with the toes pointing towards the entrance. Understand?" (Chottomatte, Tomo-chan, kutsu o soroe n to akan e. Okāsan mitai ni kutsu o soroetena, tsumasaki o genkan no hō e mukeru n yo. Wakaru.)

“Yes," (Wakaru) Tomoko replies.

“And make sure you don’t turn your bottom toward the host when you do it."(Sono toki, o shiri o oie no hito ni muken yō ni sen tona)

“Uh-huh."(un)

“That’s a good girl, Tomo-chan. You did so well!" (honma erai nā, Tomo-chan. Yō deki hatta.) Mrs. Isshiki praises her.

Tomoko looks small but proud. This is how Japanese children have learned the etiquette of shoe removal.

A well-mannered Japanese person aligns their shoes with the toes pointing toward the exit. It is also essential to be careful not to turn your back to the hosts while doing this. Mastering this is a mark of elegance. Having the shoes neatly aligned and facing the exit is also practical for when you leave, allowing you to slip them on quickly without having to bend down or awkwardly move them with your feet. Aligning footwear is a custom that combines graceful movement with practical efficiency.

This is similar to how people park cars. Japanese people usually back into parking spaces at supermarkets or restaurants. While it takes a little more effort to enter the space, it makes exiting much easier and safer. This is another example of the Japanese pursuit of rational efficiency. The cars neatly lined up in a parking lot look just like the shoes aligned at a home’s entryway.

Japanese Homes: Built on a Raised-Floor Architecture

Why do Japanese people take off their shoes? A common reason given is the climate. Japan is part of the Asian Monsoon region, which spans East, Southeast, and South Asia. The monsoon winds carry a large amount of moisture from the sea, resulting in heavy rainfall and high humidity.

While Southeast Asia is warm and humid all year, Japan has four distinct seasons and cold winters. Nevertheless, it endures the humid, drizzling rainy season (tsuyu), followed by an intense summer. The Japanese summer is so hot and humid that people from tropical countries often find it unbearable. Young women carry small portable fans, the elderly drink rehydration drinks like Pocari Sweat or Aquarius, and construction workers prevent heatstroke by wearing jackets that inflate like balloons with built-in fans.

In this hot and highly humid region, raised-floor architecture developed to make living more comfortable. Creating a space between the ground and the floor allows air to circulate, lowering the room temperature and humidity. Japanese homes are fundamentally built on this raised-floor style. Although Japan is far from Southeast Asia, people arrived via the Kuroshio Current, migrating from Southeast Asia through the Philippines, Taiwan, Okinawa, and Kyushu, and likely brought this architectural style with them.

It turned out that this raised-floor design, intended for hot and humid conditions, also worked well in the cold winter. The space underneath the floor helped block the cold air rising from the ground. This architectural style was well-suited to the Japanese climate. The only downsides were that animals might take up residence underneath, or ninjas might sneak in to eavesdrop! By the Nara period, famous structures like the Shōsōin treasure house, temples, and shrines were built with raised floors. In the Heian period, noble residences were built in the shinden-zukuri style, which became the prototype for Japanese domestic architecture. Since then, both nobles and commoners have lived lives where they remove their shoes or clogs indoors.

Okay, that makes sense. But a question arises: The floor is only about 30 cm (1 foot) above the ground. Wouldn’t it be easy to step up while wearing shoes? That’s true, but taking off shoes before stepping onto the floor has other benefits. If you wear shoes, the floor will get dirty with mud and soil stuck to the soles.

In the hot and humid summer, people want to be barefoot. They want to take off their stuffy shoes and socks and relax barefoot. It would be unpleasant if the floor were dirty. Many rooms have tatami mats to counter humidity, and if soil gets into the weave of the tatami, it is extremely difficult to remove. By keeping it clean, the space remains comfortable and reduces the effort required for cleaning. For Japanese people, walking on a clean floor with bare feet is a pure moment of bliss.

A Nation of Spiritual Practices: Keeping Kegare(Pollution/Defilement) Out

Today, however, shoes rarely get muddy in modern cities. You won’t see pub floors, libraries, or office floors covered in dirt; a robot vacuum cleaner can handle the mess. Yet, the Japanese lifestyle hasn’t shifted to one where people keep their shoes on inside, like in the United States. This suggests there must be another reason.

This reason is related to Japan being a nation of spiritual practices. To Japanese people, “dirt" is not just the physical mud and soil. Japan is the land where eight million gods (Yaoyorozu no Kami) reside. Besides gods, there are all sorts of yōkai (monsters/spirits) and chimimōryō (evil spirits). There are also vengeful spirits (onryō) and ghosts. As the Onmyōji (court diviner) Kamo no Yoshinori once said, “Ordinary people can’t see them, but these things exist in the world. It is enough just to know that they are there."

Moreover, old tools can become Tsukumogami, beings that are somewhere between gods and yōkai. A cat that lives long enough becomes a Nekomata (a fork-tailed monster cat). Historical figures like Sugawara no Michizane and Emperor Sutoku were elevated from human status to gods. There are also the God of Poverty (Binbōgami) and the God of Plague (Yakubyōgami). In short, the world is full of spiritual beings. Some of these beings can have a negative impact on people, leading to bad luck or making them prone to illness.

Once a person leaves the house, the possibility of encountering these malicious entities increases. Historically, the Japanese feared encountering such things. If encountered, they might cling to the body. Japanese people call these negative attachments Kegare (defilement, pollution, or spiritual impurity)and strongly dislike them. If they realize they have been contaminated, they perform misogi(ritual purification) or oharai(exorcism) to remove it. Misogiusually involves washing away the Kegare with water.

Every Shinto shrine has a water purification font (chōzuya)at the entrance. Visitors wash away any $Kegare$ or ill will attached to their bodies before praying. This is a form of misogi. The same principle applies at home: people do not want to bring anything bad inside. So, where do these things attach themselves? People walk everywhere. That’s right—it is on the soles of the shoes, which are in contact with the ground, that $Kegare$ is most likely to attach, along with physical dirt. If you step inside with contaminated shoes, the Kegare enters the room. People remove their shoes to prevent and containthat spiritual impurity in the doma(earthen floor entrance).

Kyakka Shōko(Look to Your Feet): The Place to Take Off Your Shoes

In most homes, you can tell where to take off your shoes because they are already lined up at the entrance. However, the spot can be less obvious at shrines, temples, traditional inns (ryokan), or public facilities. In such places, you will often find signs or placards that say “土足厳禁" (Dosoku Genkin – No Street Shoes Allowed) or “脚下照顧" (Kyakka Shōko), “照顧脚下" (Shōko Kyakka), or “看脚下" (Kanka Kyakka).

Dosoku Genkin literally means you must not step onto the raised area while wearing street shoes.

Kyakka Shōko, Shōko Kyakka, and Kanka Kyakka are originally Zen Buddhist terms. Kyakka means “at your feet," and Shōko or Kan means “to look" or “to attend to." Kyakka Shōko literally means “Look to your feet." The deeper meaning is a call to self-reflection and discipline, urging one to examine one’s own self and diligently pursue one’s practice.

However, when this phrase is displayed on a sign, it simply means to “mind your feet." In other words, when you see this sign, take off your shoes.

The Japanese custom of removing shoes is based on a blend of practical rationality (keeping the living space clean) and a spiritual reverence (fear of bringing in spiritual impurities). Therefore, the “No Street Shoes" rule must be strictly followed.

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません