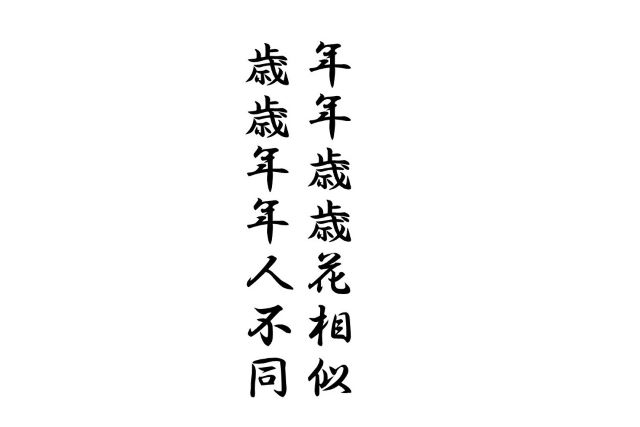

Japan – Discovering Zen Words – Today’s Best Word is “年々歳々花相似 Nennen sai sai hana ai nitari Nen nen sai sai hito onazikarazu”

Zen is hard. And Zen words? Even harder.

So I go ahead and make up my own meanings—and I like them just fine.I like to think that Master Huineng, Dōgen, Ikkyū, and Ryōkan would nod gently and say, “That’s fine. That’s fine. Let it be, my friend.”

Today’s Zen word is “Nennen saisai hana ainitari Nennen saisai hito onazikarazu" It means “Flowers bloom the same way every year, but people do not the same"

The Blossoms Are the Same, but We Are Not

Every year, around the same time, the cherry blossoms bloom.

It doesn’t matter whether the world is peaceful or in pain—whether people are dancing or grieving, the blossoms arrive just the same. They don’t wait for headlines to calm down. They don’t ask if we’re ready. They simply bloom.

And somehow, even when we’re weighed down—shoulders heavy with sorrow, eyes cast low—we still stop under those trees, look up, and let the sight of those flowers lift our heads. That alone makes them worth praising.

A Chinese poet from the Tang dynasty, Liu Yuxi, once wrote a line that has stayed with us for centuries:

“Year after year, the flowers remain the same, but the people never do."

Nature is constant. We are not. We age. We change. We leave and are left behind. The cherry trees? They do not care. They simply carry on.

And yet, instead of mourning this truth—this fleetingness of life—it might be wiser to be grateful. To say: “This year, once again, I got to see the blossoms." To admire how they bloom with all they’ve got, asking nothing in return.

That seems like enough.

Zen Is Hard. That’s the Point.

Once, I picked up an English book on Zen by D.T. Suzuki. “This’ll be easier to understand than the Japanese stuff,” I told myself. After all, it was written for Western readers. Should be straightforward, right?

Wrong.

It was like hiking straight into a foggy mountain. I’d read a line and feel I’d understood something deep—then the next paragraph would slip right through my fingers like a fish wriggling free.

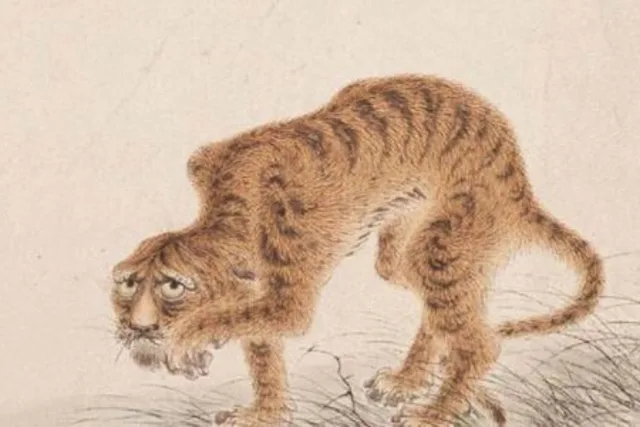

There’s a famous Zen painting of an old man trying to catch a catfish with a gourd. That’s exactly what trying to “understand” Zen feels like. You reach for it—and miss.

See, Zen isn’t about thinking harder. It’s about knowing without knowing. It’s about finding your true self, but not through intellect—because intellect is separate from the self. To really know the self, they say, you must become one with it. And how do you do that?

Well… you sit. You breathe. You sweep the floor. You chop wood. You live.

Here’s a Zen exchange I once read:

A monk asks his master,

“What is a person like before enlightenment?”

The master replies,

“Just an ordinary person.”

The monk continues,

“And after enlightenment?”

The master answers,

“His head is full of ash, and his face is covered in mud.”

Confused, the monk asks,

“What does that mean?”

The master shrugs,

“It just means what it means. Nothing special.”

…Honestly? I still don’t get it.

But maybe I don’t have to. Maybe Zen isn’t something to grasp but something to live. You don’t need a monastery or a robe. You just need the patience to sit with not-knowing, and maybe—if you’re lucky—a cherry tree in full bloom.

禅語は最高 「年年歳歳花相似」 老いを嘆くより花を愛でよう

禅は難しい。禅語も難しい。だから勝手に解釈して使っている。それで良いと思っている。案外、慧能禅師も道元禅師も、一休さんも良寛さんも「それで良い、それで良いんじゃよ、Let it be じゃ」と言ってくれそうだ。今回は「年年歳歳花相似、歳歳年年人不同」である。

年々歳々花相似たり 歳々年々人同じからず

また桜の季節がやってきた。人の世が移り変わっても、桜は毎年同じように咲く。花は、人が災害で苦しんでいるときも、平穏に暮らしているときも静かに咲いている。失意によってうつむきながら歩いていている人も、満開の桜に出会えば、花を見上げて顔を上げる。それだけでも花は素晴らしい。

唐代の詩人、劉廷芝は人生の無常を嘆いて「白頭の悲しむ翁に代わりて」を詠んだ。その4節にあるのが「年年歳歳花相似、歳歳年年人不同年年歳歳(年々さいさい花同じくして、年々さいさい人同じからず)」である。花は毎年同じように咲くが人は年ごとに老いていく。自然は変わらないが人は変わってしまう。人生は無情である。

人生は、詩人が嘆いたように自然の悠久さと比べるとたいへんに儚く短い。だがそれを嘆いても仕方がない。諸行無常を嘆くより今年もまた同じ花が見みられたことを喜びたい。精一杯咲いている花を褒めたいものだ。

禅は難解、感じるしかない

「鈴木大拙 禅(英語版)」は、禅を外国に紹介するために英語で書かれた。その本が再び日本語に訳された。外国人向けに書かれた説明書だから分かり易いはずだ、と思ったがこれが大間違い。難さはこれまで日本で書かれた本と同じである。文体も古く難解だ。その難解さは目の前に聳え立つ山のように大きい。わかったと思ってもすぐに分からなくなる。

それは掴みかけた魚がするりと逃げていくように大変にもどかしい。禅画に「瓢鮎図」がある。絵のなかで、老人が瓢箪で鯰を捕まえるようとしている。禅を理解しようとするのはこの感じだ。

禅は悟りを開くことを目的とする。悟りを開けば自己の本質を知ることができる。ただ知性によって自己の本質を理解しようとすれば、理解しようとする知性と自己の本質が別々に存在する。それでは自己の本質を知ることではない。自己の本質と知性は一体にならないといけないらしい。

これを理解するのは難しい。瓢箪で鯰である。分かったような気がするもやぱり分からない。禅僧はそれを知るために苛烈な修行をする。なんの修行もしない人間が理解できないのは当り前である。だが難しく考える必要はない。凡人は凡人なりに禅を解釈して生活に活かせばい良いのだ。私たちがそれくらいをしても許されるだろう。

ここに一つの禅問答がある。

一人の僧が師に問うた

「悟りを体験する以前の人はどんな人間でしょうか」

「わしらとと同じ普通の人間だ」

「では、悟りの後はどうでしょう」

「頭は灰だらけ、顔は泥まみれ」

「それは結局どういうことですか」

「ただそれだけだ、大したことはない

う〜ん、なんだか。やっぱりわからない。

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません