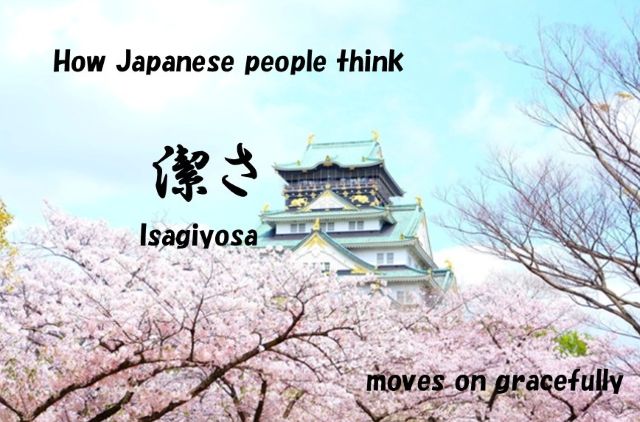

Japan Discovery How Japanese people think “潔さMoves on gracefully”

The Japanese love for cherry blossoms (sakura) is bafflingly intense. When spring rolls around, the whole country practically boils over with excitement. It’s insane! TV stations air daily bloom forecasts, and reporters stand in parks, zooming in on tiny buds. Companies, bars, and dinner tables are all buzzing with sakura talk:

“How are the blossoms looking this year? Think they’ll be ready by next Saturday?"

“It’s almost sakura season, huh? I wonder when they’ll finally pop."

“I heard it’s already 70% bloomed!"

“Ugh, I totally want to go cherry blossom viewing!"

The Japanese Obsession with Sakura

The Reason Behind the Love

This is how it is. The entire nation turns pink even before the flowers actually bloom. Naturally, a country this obsessed is dotted with countless famous sakura spots: Ueno Park in Tokyo, Osaka Castle, Maruyama Park in Kyoto, Asuwa River in Fukui, the thousand trees of Yoshino, the Kawazu sakura in Shizuoka, Hirosaki Castle in Aomori, Goryokaku in Hokkaido, and the Taki-zakura (Weeping Cherry) in Miharu. The list goes on and on.

Once the flowers do bloom, the fun really starts with O-hanami (cherry blossom viewing parties). People claim spots early in the morning, even if only a few flowers are out or the night is freezing. Then they proceed to get tipsy. In colder regions, they even bring out kotatsu (heated tables) for the party! When those scenes are broadcast on TV, even more people rush out for O-hanami. It’s a classic sign of spring.

Why this national craze? Sure, sakura are beautiful. The pale pink delicacy and faint fragrance when they first appear are lovely. At full bloom, they are gorgeous, painting all of Japan in shades of pink. But there are other beautiful flowers: the plum and apricot blossoms that bloom earlier, and now the dogwood. Yet, sakura get the VIP treatment.

This intensely admired flower, however, doesn’t stick around. It watches all the obsessed people, then vanishes in only about two weeks. One moment there’s a blizzard of petals (Hanafubuki), the next, it’s gone. It’s an astoundingly clean and graceful departure. And that is what strikes a chord with the Japanese heart.

Isagiyosa: The Aesthetics of a Clean Exit

For the Japanese, Isagiyosa (潔さ) is a deeply important concept. Isagiyosa refers to things or landscapes being pure and clean, but also encompasses decisiveness, lack of lingering attachment or regret, moral integrity, and innocence.

Above all, it’s about “having no regrets" or “leaving without attachment." The cherry blossom’s magnificent, swift, and clean surrender is seen as the ultimate embodiment of this very Japanese ideal.

A phrase similar to “regretful" or “lingering" is “Ōjōgiwa ga warui" (往生際が悪い), literally meaning “poor at accepting the time of death." Originally a Buddhist term for losing faith at the point of death, it has evolved to mean “being a sore loser"—struggling pointlessly when defeat is certain, or refusing to honestly admit a mistake. This, too, signifies a lack of isagiyosa.

In Japan, people who are sore losers or cling to things with lingering attachment are not respected. Take a former Japanese prime minister, for example: someone who continues to cling to their position despite losing election after election is generally not respected. Fighting on, believing in a comeback, isn’t bad. But once it becomes clear that a recovery is impossible, one must retreat cleanly. Being “un-clean" (isagiyokunai) invites contempt. The Japanese fear this feeling of shame.

The Fearless Pirates and the Samurai Code

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, there were Japanese pirate groups who raided the coasts of China and Korea. The victims called them “Wokou" (倭寇), using the derogatory Chinese term “Wo" for Japan. The Wokou eventually became multinational pirate gangs, including Chinese and Portuguese members, but the Japanese within them were particularly feared.

They were terrifying because they would charge the enemy without fear of death, fly into a rage if their honor was tainted, and commit suicide (jijin) if disgraced. Their disregard for their own lives was eerie and incomprehensible to foreigners. The core belief was: “Choose death over living in shame." This very phrase appears in the Hagakure, an 18th-century samurai code of conduct.

The Japanese people of the past valued honor over life itself. They chose a clean death over clinging to life.

On the battlefield, they fought as “Shibyo" (死兵) or “dead soldiers"—men who fought believing they were already dead, like zombies. Imagine being charged by a horde of soldiers like that; it’s terrifying. Ironically, the soldiers who became Shibyo had a higher chance of survival; the ones who were hesitant and “regretful" were often the ones who died. So, what happened to those men if, by some mistake, they couldn’t go to war?

Honor Over Life

Not participating in battle was extremely dishonorable and shameful. In such a case, the samurai would commit Seppuku (ritual suicide) to clear their shame. The same went for those who were wrongly accused. They would clear their innocence by dying.

This seems strange to us today. Shouldn’t you clear your name by living? Dying leaves the accusation uncleared and the dishonor intact. But people then saw it differently.

“This accusation is utterly unacceptable, and I shall clear my name with my life."

“I accept your resolve."

People sympathized with the isagiyosa (cleanliness) of risking one’s life without making excuses, and the person’s honor was restored. This action wasn’t limited to the samurai. Until farmers were forbidden from committing seppuku in the Edo period, they, too, took their own lives to protect their honor. Being clean and decisive to protect one’s honor was a critical code of conduct.

While the tendency to disregard life has decreased since Western humanism was introduced, the reverence for isagiyosa still lingers.

Isagiyosa and the Dislike of Debate

This philosophy of respecting isagiyosa is said to have originated in the Kamakura period (12th-14th century), when the warrior class took power. Warriors, specialists in combat, were constantly aware of death on the battlefield and strived to fight cleanly. This mindset, combined with the Buddhist view of mujō (impermanence of all things), gave rise to the philosophy that values purity, fleeting beauty, and isagiyosa.

The Japanese aversion to debate also stems from this philosophy. When someone drones on about their views, or refuses to admit they’re wrong and keeps making excuses, the Japanese reaction is often to shut down the conversation with a quiet, “Mō ii yo" (That’s enough, I’m done with you). That person is being un-clean in their clinging. At that point, action is preferred over endless talk. Just be warned: if you keep debating, the Japanese person might just snap!

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません