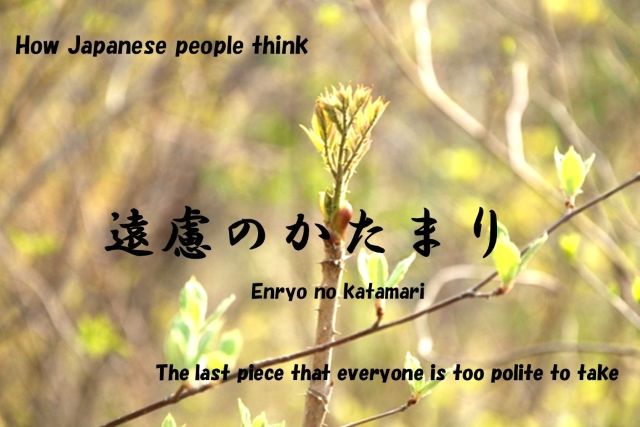

The Last Piece Dilemma: Understanding Japanese Deference (Enryo)

I went to McDonald’s with my friends and we ordered burgers, a McShake, and fries. The conversation was flowing and we totally lost track of time. Suddenly, I look down at the table and there’s just one French fry left. I totally want it, but they might be thinking the same thing. What should I do?

We ordered xiao long bao at Din Tai Fung. It was so fun chatting while drinking Taiwanese beer. All of a sudden, I realize there’s only one soup dumpling left in the steamer basket. Everyone’s eyes are glued to it. I want it, but I feel awkward reaching for it. What’s the move?

The Ritual of Concession

The Japanese call that last remaining piece of food the “Enryo no Katamari," which literally means the “Chunk of Restraint" or “Lump of Hesitation." So, who actually gets it?

If you’re in Kyoto, it usually wraps up like this: The person who first points it out and calls it the “Enryo no Katamari" is often the one who ends up eating it.

The Kyoto Vibe:

Woman A: “Aw, the Chunk of Restraint is still here. What should we do?" (Ma Enryo no Katamari ga nokottaharu wa dosyo)

Women B & C: “You should go ahead and eat it!" (anta ga tabetara yoiyan)

Woman A: “Really, is that okay? Thanks so much!"(honma eenon ookini)

If you’re in Osaka, it’s a bit more direct:

The Osaka Vibe:

Man A: “Oh, look at that! The Enryo no Katamari! Can I take it?" (Oh Enryo no Katamari yanke Ore morote ee)

Men B & C: “Yeah, sure. Go for it."(Eeyo Tabete)

In Kyoto and Osaka, it’s considered poor manners to just snatch the last piece without asking. The idea is that everyone probably wants it, so you hold back out of courtesy. That final piece becomes the physical embodiment of everyone’s restraint—that’s why it’s called the “Chunk of Restraint."

If you truly want to eat it, you need the group’s official approval. This is where that little ritual comes in. Japan is a land with millions of gods (Yaoyorozu no Kami) and all kinds of spirits and folklore. In daily life, people perform little “rituals" like this all the time!

The Ritual of the “Chunk of Restraint"

The ritual starts when someone who really wants that last piece notices it and proclaims the “Enryo no Katamari." Those who have decided they won’t eat it out of politeness, or those who are simply too full, will pretend they haven’t noticed it from the beginning.

“The Chunk of Restraint is here. What should we do?" “Looks like the Enryo no Katamari is left."

This proclamation is actually an indirect way of declaring that they want to eat it. When the others hear it, even if they secretly want it too, they have to concede. It’s essentially first-come, first-served. With a slight sense of regret, they must give their approval:

“Oh yeah, why don’t you go ahead and take it?"

“You’re right, it’s fine if you eat it."

Upon receiving this permission, the original person reaches for the final piece.

“Oh, really? Are you sure?"

“Thanks, I’ll take it then."

A child might say, “I want some too!" but adults rarely say anything like that. It seems like such a hassle—why not just say you want it from the start?

The reason they do this complicated dance is simple: they want to avoid conflict over food. If one person directly claims it, it might trigger a grab for it, with others saying, “Hey, I want it too!" This ritual is designed to prevent a struggle. Japanese people prioritize resolving things by deferring to others and reaching a mutual agreement. The most important thing is to avoid making waves (namikaze o tatenai).

Kids vs. Adults: The Janken Solution

Kids, however, don’t have the adult’s sense of restraint. They express their wants purely. If parents are around and there’s an age gap, the older child is usually forced to give in. “Your little brother gets it, so you hold back," or “You’re the big sister, so give it to him." This is totally unfair to the older kids, but that’s just how it goes.

If it’s just the kids, they settle it with a round of Janken (ジャンケン).

What is Janken?

Janken is the Japanese version of the game known in English as Rock Paper Scissors (RPS). The winner is determined by showing one of three hand signs: a rock (Guu), a pair of scissors (Choki), or paper (Paa).

- Rock (Guu): A closed fist.

- Scissors (Choki): The index and middle fingers are extended (like a peace sign).

- Paper (Paa): An open, flat hand.

The rules are the same: Rock beats Scissors, Scissors beats Paper, and Paper beats Rock. Each sign has one opponent it can beat and one it will lose to—a classic three-way deadlock.

The Janken Call & Rules

The game can be played by any number of people. Everyone decides what they’ll throw, and then they all reveal their hands simultaneously on the final word of the chant:

“Saisho wa Guu! Janken Pon!" (Lit: “First is Rock! Janken Pon!")

The phrase “Saisho wa Guu" is just for rhythm, not a command to throw rock.

If there are only two players, the one who throws the stronger sign wins. If both throw the same sign (e.g., Rock vs. Rock), it’s a tie, which is called an “Aiko", and you start over. The next chant is: “Aiko desho!" (Lit: “It’s a tie, right?").

With three or more people, an Aiko happens more often:

- When all three signs (Rock, Paper, and Scissors) are thrown.

- When everyone throws the same sign.

A round is only settled when exactly two types of signs are thrown. For example, if three people throw Paper and one person throws Rock, the Rock player loses and is out.

The Critical Timing Rule

Since the goal is to surprise your opponents, everyone tries to hide their hand until the very last moment. But be careful: if you throw your sign too late after the “Pon!" call, it’s considered an unfair move, called “Atodashi" (late throw), because it looks like you waited to see what everyone else threw. Atodashi is an automatic loss!

Cultural Insight

The Janken method is used to fairly settle disputes and allocate resources (like the last piece of cake!) precisely because the adults refuse to resort to the simple, direct claim that a child might make. It’s a structured, randomized way to make a decision without breaking the group’s harmony.

Do you want to continue with the next part of this cultural journey?

Global Game, Local Solution

It’s true that Janken-like games have gone global, and there’s even an organization called the World Rock Paper Scissors Society (WRPS). However, kids in Japan use Janken purely for practical reasons, completely unrelated to any official authority.

Imagine the scenario:

Boy A: “It’s the last one! I want to eat it."

Boy B: “No way, I want it!"

Girl C: “I want it too!"

Girl D: “Let’s do Janken!" Everyone: “Yeah! Winner takes all!"

Everyone: “Saisho wa Guu! Janken Pon!"

Girl C: “I won!"

Everyone: “Shoot, I lost."

This is how children cleverly avoid conflict. When they get a little older (around junior high), they might also use Amidakuji (a form of lottery), but that’s a topic for another time.

The thing is, Japanese kids don’t debate much. They don’t engage in philosophical arguments like, “I want to eat this one piece, therefore it exists," or “It is the correct path for me to consume this." Instead of debating, they learn ways to avoid conflict, moving from simple Janken to the adult concept of Enryo (restraint/deference).

What Does Enryo Actually Mean?

So, what exactly does the “Enryo" (Restraint/Deference) in Enryo no Katamari mean?

Enryo is the act of restraining one’s actions or opinions out of consideration for others’ feelings. It’s about prioritizing a smooth, harmonious relationship with others over one’s own immediate desires. Enryo is highly valued because it helps society run smoothly. It’s typically expressed through deferring to others (yuzuriai).

You see this deference everywhere in Japanese society: people stepping back to let others enter a shop first, or offering a seat to someone else. They’ll extend a hand and say, “Go ahead, dōzo!" and the other person will counter with, “No, dōzo, you first, osaki ni!" When they finally accept the deference, they often give a slight, grateful bow (pekorito).

The Invisibility of Agreement

This deep-rooted culture is incredibly confusing for foreigners, especially those from continental cultures where asserting one’s opinion to find a compromise is the norm. It’s like a Sumo match where the two wrestlers stand apart and just keep saying, “You first!"

In a real sport, the referee forces the issue: a Sumo referee yells “Hakk-e-yoi!" (Get going!), a boxing referee shouts “Fight!," and a Judo referee gives a “Shidō" (penalty) for non-engagement. Faced with the Japanese deference, you just want to scream, “How are you ever going to reach a conclusion? Is this done by telepathy?!"

So, how does this process of deference resolve itself? Where is the compromise?

Honestly, the answer is that it’s entirely determined by the vibe and atmosphere among the people involved at that moment. With the Enryo no Katamari, the person who first points it out usually gets the piece. But with things like yielding seats or entry to a shop, the person who has the strongest will to concede ends up “winning."

It’s strange, isn’t it? The person with the stronger will loses (the object), instead of gains.

Why the Culture of Deference?

Japanese people resolve things by yielding to one another. Why did this custom evolve?

Part of it is due to Japan historically having abundant water and food resources. It was simply more cost-effective to yield than to fight over resources. Being a Buddhist country also played a role. Buddhism emphasizes compassion and consideration for others, promoting the avoidance of conflict.

In contrast, continental societies often had many ethnic groups battling over scarce water, food, and land. Their societies were built on the premise of taking; if you didn’t assert yourself, you got nothing—and yielding meant losing. Even if modern civilization and laws prohibit outright taking, the necessity to assert your needs remains. The culture of deference and the culture of taking are fundamentally different.

A Word to Foreigners

For foreigners living long-term in Japan, this culture of deference can become a major source of stress. People yield and yield, but somehow, things get decided without anyone ever clearly asserting an opinion, which can lead to feelings of alienation.

However, understand this: The Japanese people are not trying to alienate you; they are simply practicing yuzuriai.

This feeling of deference is difficult to grasp if you weren’t raised in this culture. But simply knowing this mindset exists can reduce your stress. When you know about it, you start to notice all the little acts of Enryo happening in daily life. When you see it happening, you’ll start to get the feeling.

Next time you’re out to eat and you see that last piece, try saying “Enryo no Katamari." You will win the right to eat the last piece and a laugh from your friends.

There is a Japanese proverb about leaving food:

“When you find a stem of taranome (Angelica Tree sprout) in the mountains, you should leave one for yourself, one for the next person, and one for next year."

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません